Date: Wednesday December 04th, 2024

Time: 08:55:53 PM MST

From: @vga256

Keywords: programming, history

Subject: Where Exigy began

Time: 08:55:53 PM MST

From: @vga256

Keywords: programming, history

Subject: Where Exigy began

Way back in the mid-90s when I was a teenager, I worked a couple of summers at a new regional ISP that served the sub-arctic and arctic regions of northern Canada. The ISP, Snowshoe Inn Micro, was located in the village of Fort Providence - a place of around 500 people. Aside from going fishing along the Mackenzie River shoreline, or wandering around its dusty dirt roads while the midnight sun rounded the horizon, there wasn't much to do in the evenings after work.

Instead, I spent almost all of my hours back in the office playing Quake deathmatch and chatting with friends on IRC. Seeing me while away my time with games, my boss made an offer: he'd teach me how object-oriented programming using Microsoft Visual Basic 3.0, or just 'VeeBee'.

He taught me the IDE using a Pair Programming style - I sat left-seat, typing in variable names while he sat in the co-pilot's seat, quietly offering suggestions and asking questions. For one month, every single night, he guided me through building a VB application - an image viewer/photo gallery - and taught me OOP concepts like classes and encapsulation. After I got the hang of it, I began programming my own applications and games after work, and into the new school year. I can safely say that without his mentorship, I would have never become a programmer and game developer later in life.

Visual Basic led me to Borland Delphi (Object Pascal); Delphi led me to Macromedia Director (Lingo); and Director led me to Macromedia Flash (ActionScript). With all of these IDEs and languages, working via drag-and-drop components and objects was the central metaphor. The "command line" attitude that was typical of MS-DOS and UNIX programmers was hung up at the door, and thinking user-experience first was the core value.

Fast-forward 25 years ...January 2024... and I once again found myself hungry for an all-in-one IDE and game development toolkit. I spent two years with Unity, and found cold comfort with its 3D-only and poor UX philosophy. Godot, though more thoughtful towards beginners, suffered greatly from its 3D metaphor. web.archive.org/web/20180620234954/http:polycode.org/>A very unique IDE called Polycode was incredibly promising, but was abandoned by its master after a few years of development. IDEs like Tumult Hype were so deeply reliant upon Javascript that they proved useless for game development. Adventure Game Studio - though very amenable to visual development - was so deeply tied to making Sierra and LucasArts adventure games that it was almost useless for something as simple as Tetris.

In short, there were no visual development environments out there to make the kinds of simple, 2D games that I grew up playing in the 90s. Games modelled on Maxis's Sim Farm, Sim Earth and Sim Life, were incredibly frustrating to build with modern tools. Something that might have taken a week to build in Visual Basic would now take two months in Unity. That kind of development cycle is death for small development studios.

It was now April 2024; three months into the launch of Studio Tomodashi, and I had no way forward for making the kinds of simple shareware games I wanted to make. I needed an IDE and toolkit that didn't exist anymore.

So I decided to start making it, with only a vague idea of what I wanted, and no idea how to build any of it.

First commit: Point and click for tile type change is working. by vga256 Apr 3, 2024 at 3:27 PM

And here it is: the first build of what would eventually become Exigy. Green grass, white snow, and brown dirt tiles rendering randomly.

Instead, I spent almost all of my hours back in the office playing Quake deathmatch and chatting with friends on IRC. Seeing me while away my time with games, my boss made an offer: he'd teach me how object-oriented programming using Microsoft Visual Basic 3.0, or just 'VeeBee'.

He taught me the IDE using a Pair Programming style - I sat left-seat, typing in variable names while he sat in the co-pilot's seat, quietly offering suggestions and asking questions. For one month, every single night, he guided me through building a VB application - an image viewer/photo gallery - and taught me OOP concepts like classes and encapsulation. After I got the hang of it, I began programming my own applications and games after work, and into the new school year. I can safely say that without his mentorship, I would have never become a programmer and game developer later in life.

Visual Basic led me to Borland Delphi (Object Pascal); Delphi led me to Macromedia Director (Lingo); and Director led me to Macromedia Flash (ActionScript). With all of these IDEs and languages, working via drag-and-drop components and objects was the central metaphor. The "command line" attitude that was typical of MS-DOS and UNIX programmers was hung up at the door, and thinking user-experience first was the core value.

Fast-forward 25 years ...January 2024... and I once again found myself hungry for an all-in-one IDE and game development toolkit. I spent two years with Unity, and found cold comfort with its 3D-only and poor UX philosophy. Godot, though more thoughtful towards beginners, suffered greatly from its 3D metaphor. web.archive.org/web/20180620234954/http:polycode.org/>A very unique IDE called Polycode was incredibly promising, but was abandoned by its master after a few years of development. IDEs like Tumult Hype were so deeply reliant upon Javascript that they proved useless for game development. Adventure Game Studio - though very amenable to visual development - was so deeply tied to making Sierra and LucasArts adventure games that it was almost useless for something as simple as Tetris.

In short, there were no visual development environments out there to make the kinds of simple, 2D games that I grew up playing in the 90s. Games modelled on Maxis's Sim Farm, Sim Earth and Sim Life, were incredibly frustrating to build with modern tools. Something that might have taken a week to build in Visual Basic would now take two months in Unity. That kind of development cycle is death for small development studios.

It was now April 2024; three months into the launch of Studio Tomodashi, and I had no way forward for making the kinds of simple shareware games I wanted to make. I needed an IDE and toolkit that didn't exist anymore.

So I decided to start making it, with only a vague idea of what I wanted, and no idea how to build any of it.

First commit: Point and click for tile type change is working. by vga256 Apr 3, 2024 at 3:27 PM

And here it is: the first build of what would eventually become Exigy. Green grass, white snow, and brown dirt tiles rendering randomly.

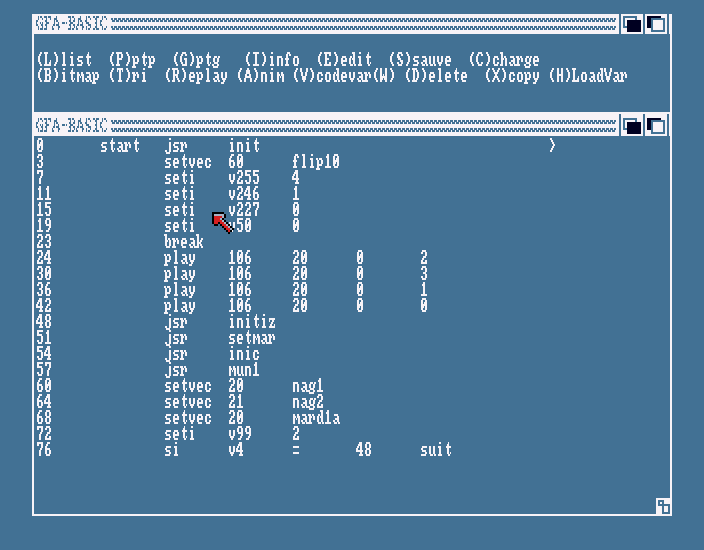

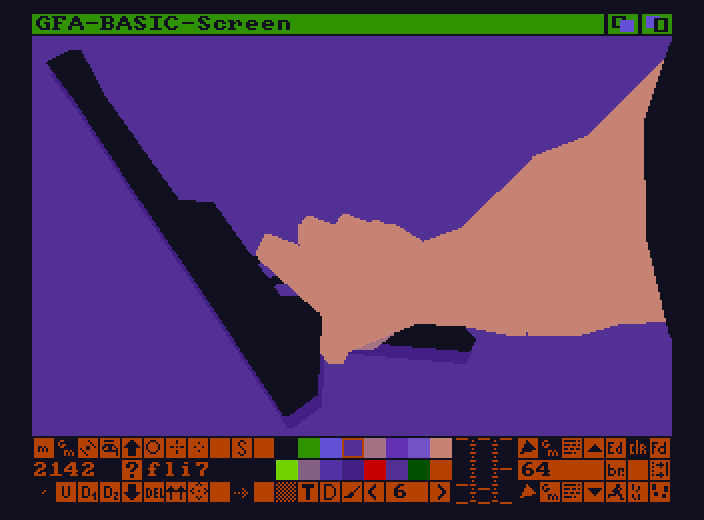

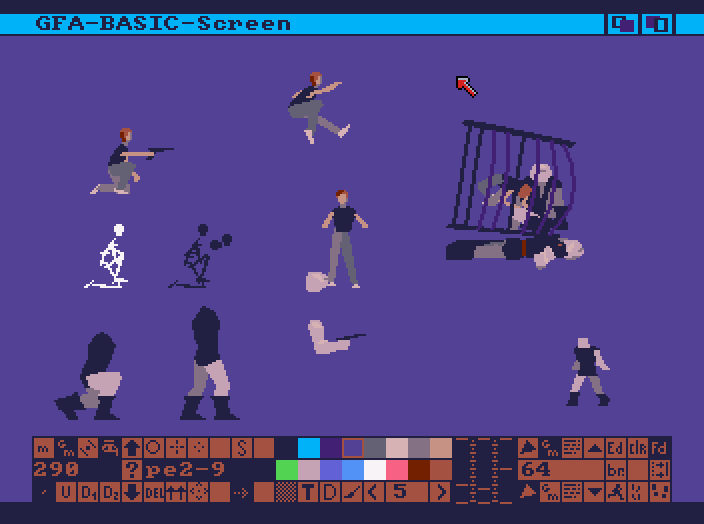

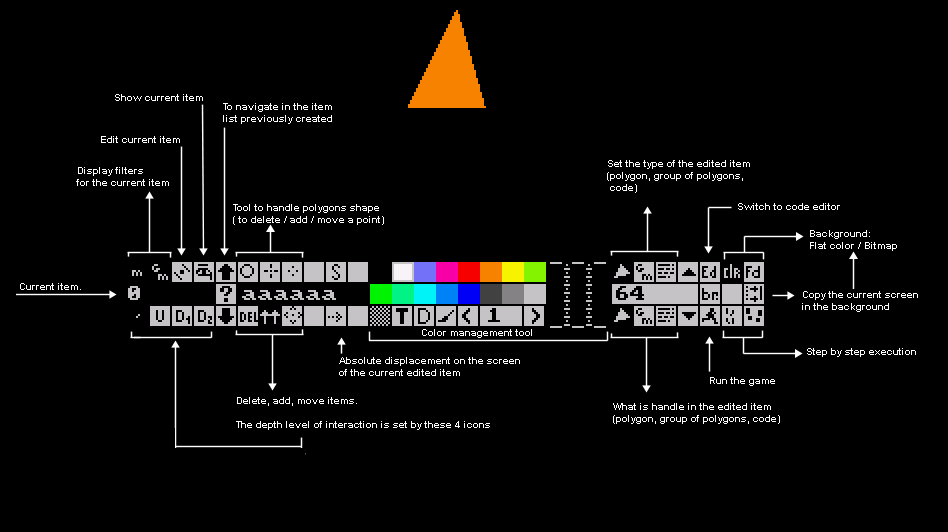

Mercifully, Chahi provides a quick reference for the editor. Here we can see just how completely functional the interface is: you can do everything on the main screen.

Mercifully, Chahi provides a quick reference for the editor. Here we can see just how completely functional the interface is: you can do everything on the main screen.